Best practice for re-siding a home calls for stripping off existing siding, then installing a good weather barrier. This can decidedly complicate a new siding job on an existing house. Instead, the industry has migrated towards what is widely marketed as an easy fix and a way to improve thermal performance and water resistance at the same time: installing fan-fold foam board over existing siding. But if it’s not applied properly, this route may lead to more problems than it fixes.

Not Insulation

At about ¼ inch thick, fan-fold foam board adds only R-1 to R-1.5 to the wall system, a negligible insulation improvement. Foil-faced products often promise higher R-values, but that is false advertising. There may be some radiant effect that can reduce cooling loads, but only when a foil-faced material is installed with a minimum ¾-inch air space in front of it—an option that requires strapping the wall before hanging the siding.

According to foam-board manufacturers, the advantage of fan-fold is really that the board provides a consistent surface over the old siding, eliminating cracks and crevices that lead to energy-robbing drafts. All manufacturers recommend taping the foam to help stop air leaks and prevent water that gets through the siding from leaking behind the foam. Unfortunately, tape is often overlooked by siders pushing to get the job done as quickly as possible. And even if you do tape, there may be problems.

“The danger is that you are putting an impermeable layer over the wall,” explains Steve Easley, a building-science expert who specializes in helping builders eliminate callbacks. “If the wall behind the foam ever gets wet—from a siding leak or a roof leak, even a plumbing leak from inside, or from excessive interior moisture condensing in the wall cavity, or whatever the moisture source—that wall will be very slow to dry.” Even when a perforated foam product is used, a solution that minimally improves the permeability of the foam, Easley argues that the potential for moisture problems will far outweigh the minor energy improvement afforded by the foam.

Stop the Air

The important thing to understand, says Easley, is that heat and moisture move rapidly through walls on air currents. “Stopping drafts is the best way to improve thermal performance and ensure the long-term durability of a wall system,” he says. “Far more important than a vapor barrier is how well you stop the air flow. Air carries far more moisture than vapor diffusion in any climate. So when weighing your options, you really should be thinking about the best way to stop air leaks.” The vapor barrier becomes a problem when it prevents a wall from drying out. If a wall gets wet, the only way it can dry is by evaporation. “You want a permeable wall that can dry out before mold, mildew, or rot takes over,” Easley says.

Continuous Exterior Insulation

How about thicker foam? These days, many new homes are built with rigid foam on the exterior sheathing—a key thermal improvement that breaks the direct line of conductive heat flow through wall framing. Continuous exterior insulation works well for new construction when the walls are designed to dry to the interior. This means they have no interior vapor control layers, especially no vinyl wallpaper or vapor-blocking paints.

Remodeling is a different animal. If you install foam on the outside of an old house, and the interior walls are covered with vinyl wallpaper or have a build-up of interior paint from years’ and years’ worth of repainting, you’ll have a wall system that won’t ever dry if it gets wet. That will likely lead to mold or rot—liability no one wants to incur.

Continuous exterior foam can be retrofit to existing homes, but doing so without incurring risk requires careful attention to the interior walls. The thicker foam also complicates how you finish around windows and doors and is best done as part of whole-house rehab that includes new windows and doors, as well.

You also have to install enough foam. Because fan-fold doesn’t really do anything for thermal performance, there remains a risk of condensation. The same applies to too thin a layer of rigid foam in a cold climate: The sheathing remains cold, so there is a potential for water to condense on the inside surface—a quick way to start a mold farm. (To learn more, see “Avoiding Wet Walls” in The Journal of Light Construction, May 2017).

Where’s the Water?

“Also think about how you’re changing the water flow when installing new siding,” Easley says. “J-channel, in particular, rechannels the water. Do you know where it’s going? Do you know it’s draining away from the wall? The only way to know for sure is if you strip off the existing siding, wrap the walls with a permeable housewrap, and flash the windows.”

Although many homeowners will be reluctant to pay for the tear-off, anything less is risky, argues Easley. It’s really the only way to adequately control the water, and it will provide a good opportunity to improve air-sealing, which will go a long way toward improved comfort—a factor that may help sell the larger scope of work.

As for the insulation, if the walls are completely uninsulated, either dense-pack cellulose or fiberglass blown into the cavities is a simple yet effective option, though this may be outside the scope of the replacement-siding contractor’s work.

Illustrations by Tim Healey

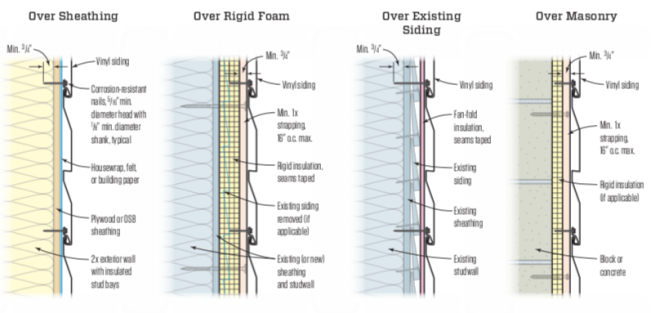

Substrate options for vinyl siding. Fan-fold foam can work over existing siding but is a poor choice and viable only if the seams are taped.

Vinyl Siding Substrates

The Vinyl Siding Institute considers vinyl siding to be part of a “water-resistive barrier system,” not a water-resistive barrier by itself. Vinyl siding stops only some of water that hits the wall. Properly installed vinyl siding is attached somewhat loosely to allow it to expand and contract with temperature changes, so it’s always subject to some moisture penetration from wind-driven rain and similar sources of water. A good water-resistive material covering the sheathing is vital for protecting the wall.

By design, vinyl works well as a rainscreen. Because the panels are hollow and have slotted nail hems, they allow sufficient airflow as well as an escape path for moisture to drain off. The spaces and materials behind the vinyl dry out readily—even without strapping as a spacer. However, if you are installing vinyl or any other siding over thick rigid foam, strapping is needed as a nail base, even if it’s not technically required as a drainage space.