Q. Is there a structural difference between full-height jacks at window openings and split jacks that fit around the rough sill?

A. John Bologna, a structural engineer and president of Coastal Engineering Co., in Orleans, Mass., responds: When the jacks on a window opening are interrupted at the sill, that framing strategy is known as the “split-jack” or “split-jamb” method, and the short answer to your question is that split jacks are structurally weaker than solid jacks.

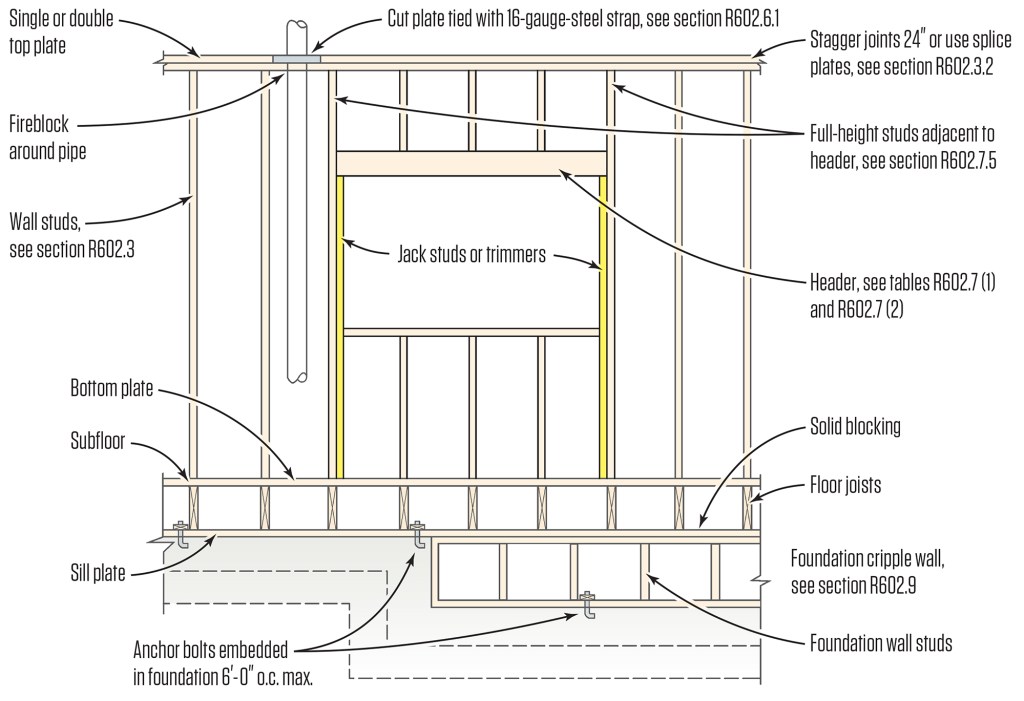

Code considerations. While the code does not directly address the issue of split jacks, section R602.3 Design and Construction does demonstrate how rough openings for windows should be framed: “Exterior walls of wood-frame construction shall be designed and constructed in accordance with the provisions of this chapter and Figures R602.3(1) and R602.3(2), or in accordance with AWC NDS.” Figure R602.3(2) (re-created below) clearly shows solid jacks (or “trimmers,” as they are commonly called on the West coast) on either side of a framed window opening, with the sill butting into the jacks.

Structural issues. Most people think only in terms of the gravity load transfer—that is, floor and roof loads transmitted through the header and into the king-and-jack-stud assembly. If you’ve framed the walls with good kiln-dried lumber, transferring those vertical loads with split jacks should not be a problem structurally. Anecdotally, I have heard of framers who used the split-jamb method with green wood. When the wood shrank across its thickness, the loads from above reportedly caused the opening to rack and the windows to bind.

But a window that operates poorly is just a small part of why split jacks aren’t a good idea. Keep in mind that the stud wall assembly is also important for resisting lateral (wind or seismic) loads. This loading is transferred into the structural frame in two directions: longitudinally, or parallel to the wall (when acting as a shear wall), and transversely, or perpendicular to the wall, when lateral loads are applied against the wall area (as with a sail).

When you’re analyzing jack requirements, this second type of loading is most relevant. In a framed wall, the studs act in concert with the cladding system, transferring horizontal wind forces into the horizontal floor and roof diaphragms. This transfer occurs in bending along the strong axis of the studs and into the deck above and below. At window and door openings, the common stud spacing is interrupted, and the wind pressure on the window is transmitted to the structural elements around all four sides of the rough opening.

On smaller openings, a single king stud and continuous jack stud are usually OK, but for larger openings, more than one king stud may be required. Think of it this way: When the common studs are removed to create an opening, king studs and jacks are asked to assume the loads that would normally be resisted by the common studs. Those loads become concentrated at the king-and-jack-stud assembly. The studs at the sides of the opening are doing the work of three or four studs missing from the opening. When jacks are split, they cannot help to resist those transverse loads, which then become concentrated mainly on the king studs.

In high-wind areas like the coast where I work, we often beef up the jack-stud assembly by installing additional king studs to form a stronger jamb assembly. In some cases, we call for engineered-lumber posts with proper connection hardware to help transfer the forces. A good rule of thumb is to add an extra stud to each jamb stud assembly for every two studs that are removed for the window. If the opening is 5 feet wide and you’ve taken out four studs, add two studs to the assembly on each side.