Sawdust. It’s everywhere carpenters are. Even a short stint in a shop or on the job confronts you with the long-standing issue that it accumulates rapidly and in large quantities. Collecting it or moving it out of the way, however, merely postpones the ultimate question: what to do with all that waste?

The same question emerged on a larger scale in the history of the wood industry. In the 19th century, that industry disposed of waste as many others did: Companies piled it up or dumped it somewhere else. But as the wood industry grew, the magnitude of the problem became daunting. Reliable calculations throughout the 20th century suggest that 40% of a log by weight is wasted in the conversion to lumber. On average, every thousand board feet of lumber sawn produced one ton of waste, much of that bark and chips, but almost half sawdust and other fine residues. What to do with it? Early mills built on rivers and streams simply poured it into the water downstream, hoping the current would whisk it away. With increased tonnage, though, wood waste accreted along shores and behind obstacles, creating massive blockages and damaging fish populations. Lawsuits followed, pitting fishermen against sawmills.

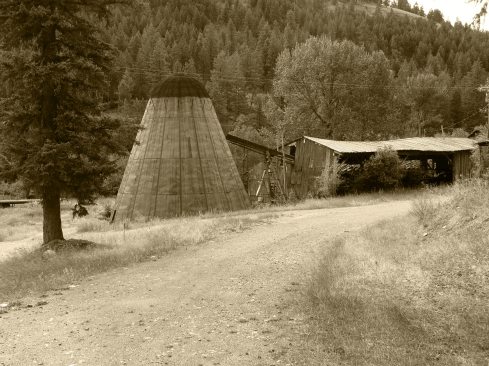

Steam-powered mills eased the trouble a bit; some waste could be burned to produce steam to run the engines. But the volume of waste far exceeded that demand, resulting in huge sawdust piles. In fact, the American spirit of competition created rivalries around who had the biggest one. Ripley’s Believe It Or Not named Red River power plant’s waste pile in Westwood, Calif., as the world’s largest, but it was supplanted by a 130-foot-tall mound in Portland, Ore. Not to be outdone, Cheboygan, Wis., claimed its heap was the largest, covering some 12 acres and hyped at 150 feet high, though photographs and memories put the height at a more realistic 50 feet. These piles weren’t without hazards; spontaneous combustion or collapse and burial endangered anyone nearby. Anything not piled was burned in enormous “beehive burners” that roared day and night, spewing sparks and smoke. Even the growth of electric utilities burning wood waste to generate power couldn’t consume the massive volume.

Robert Ashwood

Beehive wood waste burner.

The situation was untenable; the lawsuits, danger, and cost of the waste burdened businesses. In the early 20th century, an industrial culture of efficiency emerged, exemplified by the Swift meatpacking company’s success profiting from “every part of the pig but the squeal,” and engineering societies sponsored a broad research program concerning waste. The resulting 1921 publication, Waste in Industry, surveyed the causes of and cures for waste in several trades, including building. Sawmills and industries of all sorts started to examine their waste. In 1922, The American Lumberman journal held that “the turning of waste in forest products into something worthwhile, something profitable, is of the greatest interest.” A 1927 issue of The Timberman magazine argued that “A factory having no regard for waste and no regard for economy in cutting up its lumber is lost, for … this waste if conserved would itself produce a reasonable profit. We must either utilize our waste or figure it as part of our cost.”

New uses for wood waste emerged: Finely ground sawdust—wood flour—went into linoleum, dynamite, briquettes, and fuel pellets; “hogged” waste fed pulp mills to produce newsprint and corrugated cardboard boxes; compressed sawdust was used for particleboard, animal bedding, and mulch. By the 21st century, of the 150 million or so tons of wood waste produced annually in the United States, 98% was used rather than wasted.

The timber and lumber industry success in dealing with its waste problem has given me a new perspective on my own world-record sawdust pile, though, sadly, I have not had quite the same success in reducing mine.

Keep the conversation going—sign up to our newsletter for exclusive content and updates. Sign up for free