Hundreds of homes were destroyed by out-of-control infernos this week in southern California, as multiple wildfires exploded out of control in communities from Santa Barbara to the Los Angeles suburbs. Firefighters and aircraft from around the country rushed to California, but weary firefighters held out little hope of containing the flames in the face of a worst-case combination of fire conditions: tinder-dry vegetation, difficult terrain, and hot, dry, blustery Santa Ana winds blowing at gale force out of the interior desert toward the coast.

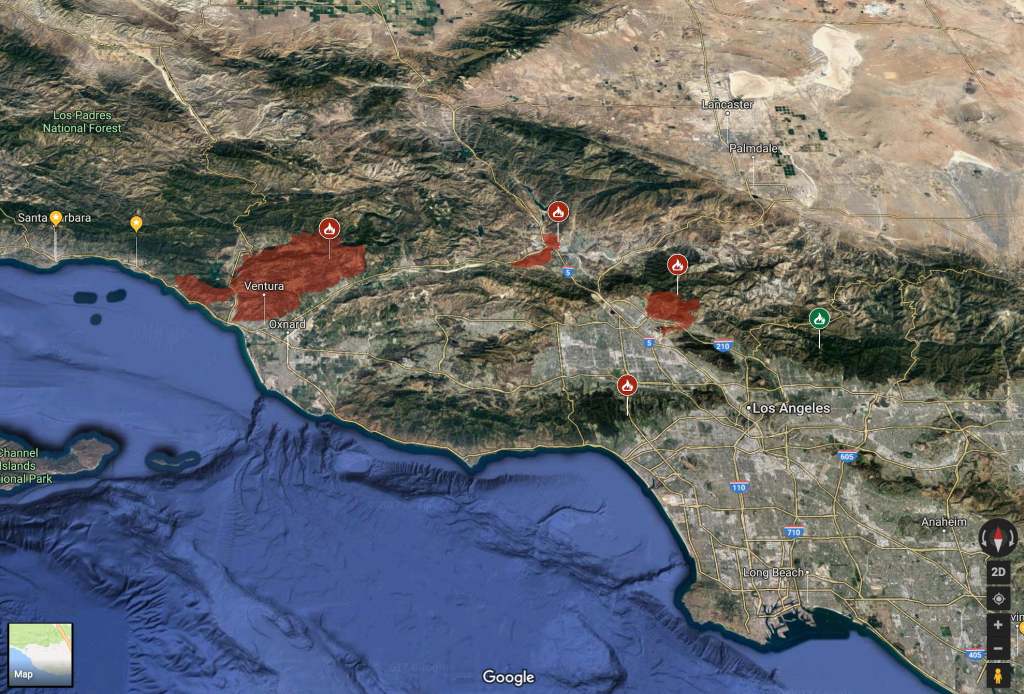

The Thomas Fire near Ventura drove thousands of people from their homes (see map, left), while the Creek and Rye Fire near Los Angeles threatened suburbs and shut down major commuting arteries around the city. See also: “Where the Fires Are Spreading in Southern California,” by K.K. Rebecca Lai, Derek Watkins, and Tim Wallace (The New York Times); “Map of hot spots: See where California wildfires are growing,” by Susan Steade (San Jose Mercury News); and “Animated map: Watch as the Thomas fire explodes in Ventura County,” by Swetha Kannan (Los Angeles Times).

By Sunday morning, firefighters had made progress on some of the region’s firelines, reported the Los Angeles Tmes (see: “Firefighters begin to turn the tide on Southern California wildfires,” by Melissa Etehad, Ruben Vives and Sarah Parvini). Still, authorities cautioned that “continued high winds into Sunday could create erratic fire conditions,” reported the Washington Post (see: “First fatality confirmed as raging wildfires spread across Southern California,” by Rob Kuznia, Max Ufberg, Soo Youn and Amy B Wang). “Red flag warnings of heightened fire risk remain in place through Sunday, when winds could peak at around 50 mph,” reported the Post. “That could combine with extremely low humidity to create severe fire conditions, as the fire’s fuel — abundant vegetation and trees — remain dry.”

December fire risk has become the “new normal” in California, warned California Governor Jerry Brown. Weather Underground blogger Bob Henson reported that current weather patterns mean there’s little chance of rain in the next few weeks (see: “No Rain in Sight for Fire-Plagued Southern California,” by Bob Henson). “There’s no sign of any thirst-slaking moisture for Southern California in the foreseeable future,” wrote Henson. “The upper atmosphere over North America is locking into a pattern with a very strong ridge near the Pacific Coast, a strengthening trough in the East, and a freight train of northwest flow and cold air funneling into the eastern half of the U.S. and Canada. This pattern will force any potential rain-making low pressure systems well north of Southern and Central California for at least the next 10 days, if current model projections hold. Some relaxation of the pattern is possible beyond that point, but there are no signs right now of any major shift toward wet Pacific storms heading for California.”

And if California’s usual winter rains finally do come, they’ll bring with them a risk of their own: mudslides, technically known as “debris flows,” on burned-out hillsides (see: “How debris flows happen,” by Raoul Ranoa – Los Angeles Times). The destructive mudslides are a typical after-effect of major brushfires in coastal California, say experts: bare soil on burned-over slopes is often mixed with tarry resins from burned chaparral plants, which combine with fine dust and rainwater to create a thick slurry that flows like wet concrete, pouring down slopes and gullies, picking up rocks and boulders, and sometimes destroying buildings in its path.