JLC: How does all that fit in with the “tuned glazing” approach promoted by some energy-conscious builders, where you might use high-gain windows to collect heat on a southern exposure, with low-gain windows on the east and west to control low-angle sun?

Mathis: You can design glazing based on orientation, but it’s not for everyone. Production builders won’t do it, because they’re going to use the same plan on different lots with different orientations. With a custom home, it can make sense. You usually don’t want to put a lot of glass facing west because the sun comes in low and you can’t shade it with an overhang, but maybe that’s where you have a great view of the mountains. Low-gain glazing can face that way without overheating.

One thing to keep in mind is that different types of glazing admit different amounts of light. That could be a problem if you have two areas of different glass at a corner. If you can see both panes at the same time, you’re going to see a noticeable difference.

But when it comes to putting high-gain glazing on the south to increase solar gain — which is what most people mean when they talk about tuned glazing — there’s a real risk of overheating. Before you go with high-gain windows on the south, you want to be sure you’ve done your heat-load calculations and double-checked them. Make sure you’ve figured your overhangs correctly, sealed your ductwork, and fine-tuned everything else. For every one instance where someone benefits from high-gain glass, there are many, many more who will be less comfortable or have higher cooling costs.

DePaola: I’m often asked why it’s so hard to find well-insulated high-solar-gain glass. The answer is that manufacturers worry about consumers complaining about overheating. They don’t want to stock it, so they don’t get many orders.

But I will say that the Canadian market has looked slightly larger in the eyes of manufacturers than it did during the building boom. The Canadian version of Energy Star rewards high-gain windows, so U.S. manufacturers may start looking at that also.

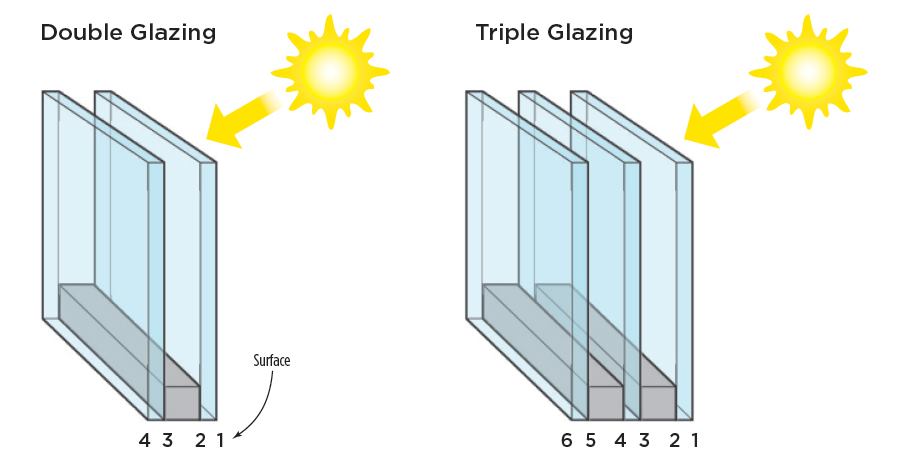

JLC: Double-glazed windows are still driving the market in the U.S., but triple glazing has been gaining popularity with some energy-conscious northern builders. Is it eventually going to take over everywhere?

Selkowitz: Most of Northern Europe has already gone to triples — that’s the norm. If you can get the window U-factors down to the 0.2-to-0.1 range, you’re already at net zero as far as the windows go. You lose some heat on a cold winter night, but you’ll make it up with solar gain during the day, even with a north-facing window that doesn’t get any direct solar gain.

Under extreme conditions, triple glazing can also make sense in a cooling climate. Say you’re in a place like Phoenix, where the temperature outside your window might reach 120°F. Depending on where you set your air conditioner, you could easily have a temperature difference of 50° between indoors and out. That’s close to the difference you’d find on a cold winter night in a heating climate.

Mathis: Triples are useful in most of Canada and parts of the northernmost U.S. In some ways, our thinking is still stuck in the energy crisis of the 1970s. The oil embargo was a huge problem in New England, where everyone heated with oil. That’s why you see a lot of triple-glazed windows there now.

But in most of America, the issue is cooling. Seven of the 10 fastest growing states are in the south. People look to the Germans and the Canadians as a model for efficient windows, but that’s not the situation faced in most of the U.S. Triple glazing makes the most sense where heating costs are much higher than air conditioning costs. Gas is cheap now and likely to get cheaper, but a lot of utilities are pretty much tapped out, especially in the south, so cooling costs are likely to increase a lot faster than heating costs in the coming years.

Carmody: One point I’d make is that the U-factors of the best gas-filled double-glazed windows have come down to 0.28 or less, which is more or less where triple glazing used to be. That’s a significant change — just a few years ago, a typical value for a good double-glazed window would have been 0.35 or so. The cost-effectiveness of going to triple isn’t always there unless you’re in a situation where you’re trying to squeeze every last Btu out of the building envelope.

JLC: What are the pros and cons of full triple glazing compared with double glazing with a suspended plastic film between the inner and outer panes of glass?

DePaola: You can put a low-E coating on both sides of a suspended film with clear glass on both sides, so you get low-E in both directions without overheating the space between the inner and outer glazing. The other big advantage to the suspended film is that it reduces weight and thickness. One reason triple-glazed windows are so expensive is that you need a thicker, stronger frame and heavier hardware. You might also need balancers to compensate for the weight, and that makes the window cost even more. If a manufacturer started cranking out suspended-film glazing units in volume, the market might eventually go to those.

Selkowitz: Most European windows use full triple glazing, but there’s no intrinsic reason why double glass with film can’t be just as reliable. Look at laminated glass — that’s a glass/polymer combination that has been around for a long time and is completely free of problems. Southwall Technologies [the only U.S. manufacturer of suspended films] used to sell the film to third parties and let them make their own glazing units, but they now have their own plant in the Chicago area.

Most films are not double-coated, but one of the advantages to film is that you can stockpile rolls of different materials and have them ready to go. That’s a lot simpler than trying to inventory large amounts of glass.

JLC: The NFRC rating system has obviously been very useful in providing basic information about window performance, but what other tools are out there for builders who want to go into more depth when selecting windows?

Carmody: Before the NFRC rating system was adopted 20 years ago, manufacturers could make any claims they wanted, but now windows have to be labeled and their performance is verified [see sample labels, facing page]. Assuming you know what your local code requires, the NFRC label lets you determine which windows meet it. It’s a very effective system. The next layer up from that would be to select an Energy Star window.

Ideally, windows would have labels that spelled out their expected energy cost, like you see on a washing machine or a refrigerator. That’s not practical because orientation, climate, and fuel costs vary so much. You can factor in all of those things with an energy modeling program like REM/Rate, but that’s a lot of work, and it’s more than most builders are going to want to do.

A more basic option that might take five or 10 minutes is to use the Efficient Windows Collaborative’s window selection tool [see screen shots, below]. It lets you enter your location, information about the glazing you plan to use — double or triple, gas-filled or not, high, medium, or low solar gain — and select a window frame type. When you’ve done that, it will give you an estimated heating or cooling cost for a typical 2,250-square-foot house with a fixed number of windows. The number is going to be rough because it doesn’t account for solar orientation or the actual house size, but we’re just about to launch an improved version of the software that allows the user to enter more of those kinds of specifics. Once you have the energy cost estimate, you can continue to a list of manufacturers and specific products that match your window selection.

If you want to spent a little more time — maybe half an hour or so — you can use a program called RESFEN [windows.lbl.gov/software/resfen/resfen.html]. It was developed by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and it lets you get much more specific in terms of size, orientation, shading, and the actual construction of the house. You also get more outputs, including peak heating and cooling demand. It’s still not as powerful as REM/Rate, but you don’t need any special training to use it.

JLC: What about the relationship between Energy Star, the codes, and the glass and window manufacturers? Can window performance keep getting ratcheted up indefinitely?

Selkowitz: That’s been the great debate for the last year or two. Energy Star used to be 10% of the market, and now it’s 70%. When the window and door criteria were revised in 2010, building codes in a good part of the country were already ahead of Energy Star. That put them in the absurd position of putting a premium label on windows that were worse than code.

The draft version for the 2014 version of Energy Star calls for U-factors of 0.27 in the north, down from 0.30. The numbers aren’t final yet, but that’s about as low as you can go without adding a suspended film or going to full triple glazing. The problem for Energy Star is that its products are required to be cost-effective. “Cost-effective” is in the eye of the beholder, but because the market isn’t demanding triples, it would be hard for them to go there.

JLC: What kinds of new technologies can we expect to see in the next decade or so? Are there any real game-changers out there?

Selkowitz: There are three main areas of research right now. One is vacuum glazing, which works like a thermos bottle — you have two sealed layers of glass separated by a vacuum to reduce conductive heat transfer [see “Vacuum-Insulated Glass Takes On Triple Glazing,” JLC Report, 10/10]. A Japanese company is already using that technology successfully outside the U.S.

A second approach has to do with ways to produce triple glazing that’s thinner, lighter, and more cost-effective than what we have now. We’re looking at ways to suspend a very thin, lightweight sheet of glass between conventional inner and outer panes without an extra set of spacers. We actually considered this years ago, but the thin glass was expensive and hard to find; now it’s mass-produced for flat-screen TVs. We’re also researching ways to bring down the cost of krypton, which is a more efficient gas fill than argon. Thin glass and krypton together could give you U-factors as low as 0.12 to 0.1 — that’s R-8 to R-10 — with about the bulk and weight of double glazing today.

The third area is “dynamic glazing,” using self-regulating electronic tinting or thermal blinds that open or close to keep heat in or out, depending on the conditions. We’re working with a major window manufacturer on that now. The key to making that work is going to be giving the window enough onboard smarts and sensors to make the right adjustments on its own without a lot of user input.