Braced Wall Lines

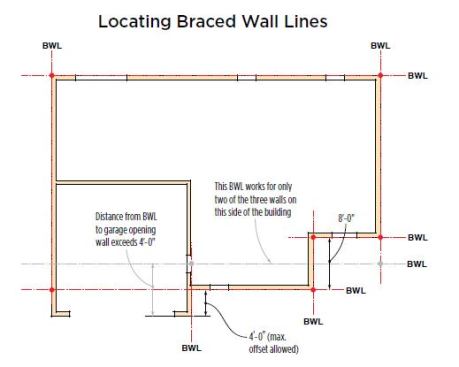

To specify the bracing in a wall of a house, you first have to establish what the code calls a “braced wall line” (BWL). The code definition is: “A straight line through the building plan that represents the location of the lateral resistance provided by the wall bracing.” In other words, BWLs aren’t the same as the actual walls; they are part of the plans, not part of the building. Actual walls do have to be close to the braced wall line, however. And in complicated plans, the locations you choose for the BWLs can affect whether your plan meets code or not, as you make choices about how to split the difference between pieces of wall that don’t quite line up with each other. That’s because a “braced wall panel” (or BWP, which is the physical bracing, as explained below) can be up to 4 feet away from the braced wall line it belongs to, but no more than that; otherwise, you can’t include it as part of the required bracing (see “Locating Braced Wall Lines,” previous page).

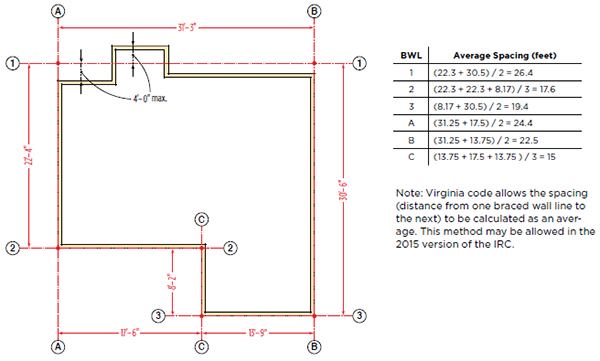

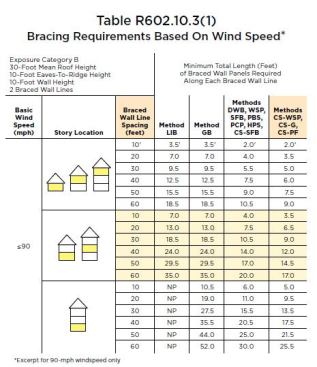

Spacing. Braced wall lines are allowed to be as far apart as 60 feet, but the spacing between parallel braced wall lines affects how much bracing they need (see “Calculating Average Spacing,” above). Braced wall lines that are farther apart experience more racking load, so they require more bracing — which leaves less room in the wall for window and door openings. In practice, if a home’s exterior walls are farther apart than 60 feet, you’re going to need to rely on some bracing from interior partitions. On the other hand, when the outside house walls are closer together than 60 feet, you still may want to count the contribution of some interior walls in order to leave unbraced lengths of exterior wall available as openings for doors and windows.

Adjustment factor. Defining additional braced wall lines carries with it an adjustment factor — you could call it a penalty. (This is one of four adjustments discussed on page 35.) If you split your braced wall panels across more lines, the total amount of bracing you need goes up. It’s a hard concept to wrap your head around, but the upshot is this: Simpler houses are easier to brace than complicated houses, and simpler bracing solutions are more efficient than complicated ones. If you can accomplish all your bracing with just two walls in each direction, there’s an advantage in doing it that way.

Even though a braced wall line is an idea and not part of the physical building, it does have to be part of the plans. The 2009 IRC says you have to show the braced wall lines on your drawings, and you also have to draw in the locations of each braced wall panel. You’re going to want to think this stuff through early on in the design process. You don’t want to thrash out a whole design idea with your clients, have them fall in love with the final version, and then find out you can’t build that patio door or bay window into your west wall because it won’t leave enough room for the bracing, or find out that the wall between your kitchen and laundry room just isn’t where it structurally needs to be. It can take multiple passes through the design process, running one after another scenario, moving windows and relocating partitions, before you get a solution that gives you the floor plan, views, traffic, egress, and elevations you want, and that also satisfies the code’s requirements for wall bracing.

Braced Wall Panels

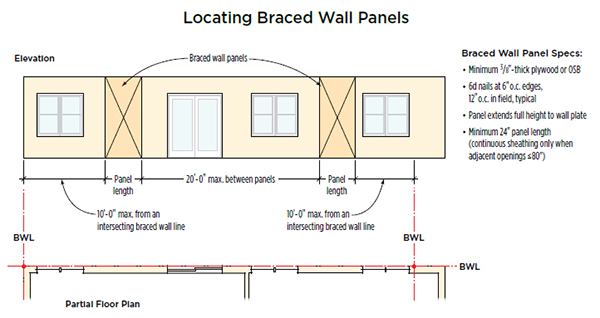

While braced wall lines are theoretical lines on the plans, “braced wall panels” are the actual physical bracing within a built wall. The code defines a braced wall panel as “a full-height section of wall constructed to resist in-plane shear loads through interaction of framing members, sheathing material, and anchors.” In physical reality, we’re talking about a short section of framed wall with plates, studs, and some kind of bracing material for stiffness. Braced wall panels have to run the full height of the wall, from bottom plate to top plate, with no interruptions for windows or doors. They also have to be a minimum length along the wall, which varies depending on the method used. Weaker materials, such as gypsum board, or weaker methods, such as let-in bracing, require more linear feet of panel to achieve the required bracing.

A braced wall panel using OSB or plywood typically has to be at least 32 inches long if the wall is continuously sheathed and the headers of openings adjacent to the panel are not higher than 80 inches off the floor. If the sheathing is not continuous but employs intermittent OSB or plywood panels, each panel typically has to be at least 4 feet long to be counted. However, there’s an exception even to that rule: Shorter intermittent panels can be included in the bracing total, but with a reduction factor applied. So while a 4-foot section of sheathed wall counts as 4 feet, you can also get “partial credit” for shorter sections: a 42-inch-long panel is worth 36 inches in your calculations, and a 36-inch panel is worth 27 inches. These reductions only apply, however, if the wall is no more than 8 feet tall; in taller walls, BWP lengths under 48 inches don’t count at all.

Advanced Methods

If you do come up short on wall space in which to install braced panels, you still may not have to go to an engineer. The latest code editions have a few advanced methods built into them that might let you gain adequate bracing in a very short section of wall:

- The “alternate braced wall” (ABW) method uses short braced-wall elements that include hold-down straps or anchors placed at wall ends.

- Method PFH, “portal frame with hold-downs,” is a way to build in bracing around wide window or door openings using very narrow wall sections with closely nailed sheathing.

- Method PFG (“portal frame at garage”) accomplishes a similar feat with garage openings, where designs commonly don’t allow enough length in the wall segments flanking the door opening to meet the minimum size for a braced wall panel.

All of these methods make up for the lack of wall length by using double studs, very close nailing, and strong anchorage at the base of the wall to create a strong, stiff structural element that resists racking.

As Brian Foley observes, there’s no way anybody is going to master the ins and outs of this difficult code section by reading one article in a magazine. But that doesn’t mean you can’t ever learn it. Whether you take a class like Foley’s all-day course or just do your own research and learn on the job, one house at a time, getting a good handle on the wall bracing rules is within reach for any capable builder. And once you do have it down, this part of the code offers you plenty of ways to build high-quality houses — and do it cost-effectively.

Ted Cushmanis a freelance writer based in Peaks Island, Maine. He is editor of the Coastal Contractor newsletter and has been a regular contributor to JLC since 1993..