I had the good fortune this year to attend “Summer Camp,” aka The Westford Symposium on Building Science, which has been held the first week of August (more or less) for the past 27 years. I feel fortunate because work and family demands don’t always allow me to attend, and because it’s so much fun. The conference sessions, organized by Joe Lstiburek, fully immerse attendees in the experience and collective knowledge of the brightest minds in building science, engineering, and practical building design in North America (and sometimes beyond). The notably fun part takes place after hours, when the conference adjourns and everyone retires to the BSC campus (and home of Joe and his wife, Betsy Petitt, whom Joe credits with organizing everything but the conference sessions, though she probably has some say in those, too). The hospitality is generous and the conversations with guests unusually inspiring.

The conference part is fun, too, if you lean toward building better, but it’s also a lot of work. The flow of information is incessant; some of it eludes my grasp, and all of it is advanced.

The following are notes from just one of the presentations. They are impressions, a riff, not a full summary or the melody itself. Any attempt to recap a presentation inevitably falls short of the live event.

Should Low Carbon Take the Lead?

John Straube opened the conference by asking: How much focus should we put on low-embodied-carbon building materials? Straight off, he acknowledged he’s new to this study and has questions around this fresh frame of reference for building science. Straube is known for his work on the design of moisture-tolerant building enclosures. (A second edition of Building Science for Building Enclosures, the seminal book he co-wrote with Eric Burnett, was recently released; the first edition, which was given out at Summer Camp circa 2005, has become my go-to resource for sorting out questions about moisture moving through building assemblies.) On this new topic, he brought an admirably open viewpoint that refreshingly didn’t feel like the preaching of a true believer.

Nevertheless, I left the session convinced that carbon reduction is the inevitable next step in the evolution of building better.

Here’s a brief recap, inspired by Straube, of this evolution to date: The energy crisis in the 1970s ushered in a new age of making buildings more energy efficient. This movement led to a raft of moisture-related disasters, like rotting structures and unhealthy, mold-ridden indoor environments, which have been the impetus for the work of many of the Summer Camp attendees (including much of JLC’s coverage of building failures since its beginning in the 1980s). Efforts to reduce energy consumption have gradually made progress, largely driven by codes, though codes, Straube noted, are based more on theory than reality due to low compliance (even in Canada). Still, the U.S. has seen a 30% reduction in household energy use since 1980. But our industry is not making much progress in reducing carbon emissions.

Operational vs. embodied. The energy consumed by a building over its lifetime is, in the new vernacular, “operational carbon,” and it’s still of critical importance for reducing carbon emissions. But the main reason our industry has made few gains in reducing greenhouse gas emissions is “embodied” carbon. Straube zeros in on the portion emitted when building materials are mined, processed, and transported, and when building products are manufactured from those materials, stored, and transported.

An attendee at the conference commented that “embodied” is somewhat of a misnomer and that a more appropriate term might be “upfront carbon.” That attendee attributed this term to Lloyd Alter, the Toronto-based sustainability enthusiast who helped popularize the term on Twitter in 2019 and whose upcoming book is titled The Story of Upfront Carbon. According to promotional materials, this book is intended to focus consumers on the “astonishing” amount of carbon used to produce everyday goods, and it explains “why we are fixated on energy efficiency, not carbon, and why this needs to change.” While the first part of that statement may be true of many of us, the second part seems dangerously close to throwing the champagne out with the cork. This opinion is mine, but I think it reflects the healthy critique of the low-carbon movement that Straube wants Summer Camp attendees to consider. To be fair to Alter and his publicists, it’s probably true we shouldn’t be “fixated,” but Straube’s presentation underscored the importance of staying rational as we move toward low carbon. Forgetting about, or moving away from operational carbon in any way, is not the way to do that.

Project-specific products and assemblies. When designers and builders select low-carbon materials, Straube urges them to evaluate specific products and assemblies, not just material types. The embodied carbon of ready-mix concrete, he explains, is more meaningful than the carbon emitted from cement; counting the carbon released making a wood I-joist is a more accurate tally than the carbon from wood.

Counting carbon. Different building materials and products emit different greenhouse gases, each with its own potency. This potency is expressed as a global warming potential, or GWP. To compare the emissions from different products, GWPs are converted to an equivalent of just one gas, carbon dioxide, or CO2e. The CO2e of products is reported by the manufacturer in a standardized format called an Environmental Product Declaration. EPDs serve as a nutrition label, so to speak, for construction materials. And while EPDs may be the most reliable documents available for evaluating the life-cycle carbon of materials, they are constantly changing as new data and new assumptions are sifted into these reports. They have an expiration date, and Straube advises specifiers to regularly check that they are consulting up-to-date data.

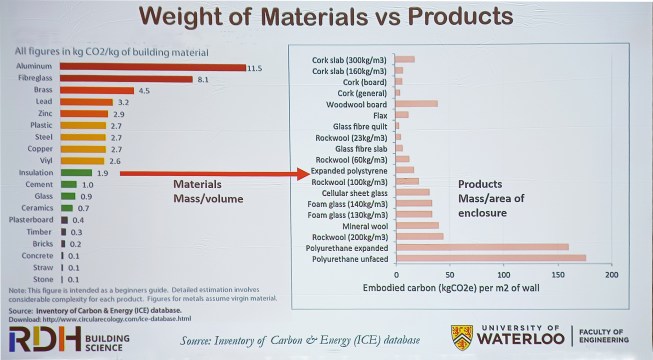

It’s also important to accurately parse the data in the EPDs. For example, the carbon emissions from raw materials are typically expressed as a function of weight as CO2e/lb or CO2e/kg. But this measure does not accurately reflect how the materials are incorporated into buildings. A better, and certainly easier, accounting for specifiers and designers is to evaluate the amount of product used in an area of an assembly, such as wall area. This is typically expressed as lbCO2e per ft² or kgCO2e per m². This difference is particularly evident when evaluating insulation and varies widely depending on the type (see image, below). In particular, Straube emphasized, any attempts to reduce the amount of insulation as a category in buildings is a fool’s quest (my term); insulation is the material that most contributes to reducing the operational carbon expended. The echoing refrain is “don’t forget operational carbon.”

The embodied carbon in a product like Rockwool, even high-density compressed Rockwool boards, is significantly lower than in closed-cell spray foam insulation (a type of expanded polyurethane foam) or polyisocyanurate foam boards (also derived from polyurethane). The CO2e/kg of insulation as a category doesn’t provide this critical detail.

Building lifespan. A full accounting of carbon reduction necessarily encompasses the whole life cycle of the building, which I find an especially refreshing reset in the building-better evolution. Focusing on low-carbon forces us to think more holistically about buildings in a way that energy efficiency often doesn’t. As an industry, or perhaps a society, we are obsessed with the dollar payback on energy efficiency—a payback measured in years, and the fewer the better. No one ever accounts for the payback on granite countertops and open floor plans, but we insist that we account for the payback on high-performance windows and increased insulation and air sealing. This pushes us to think in short bursts of time about a critical dimension of building performance. The focus on embodied carbon ropes in the entire life of the building, and the longer the better.

Decarbonizing the Grid

The biggest “aha” moments I had listening to Straube underscored the links between decarbonizing buildings and decarbonizing the grid.

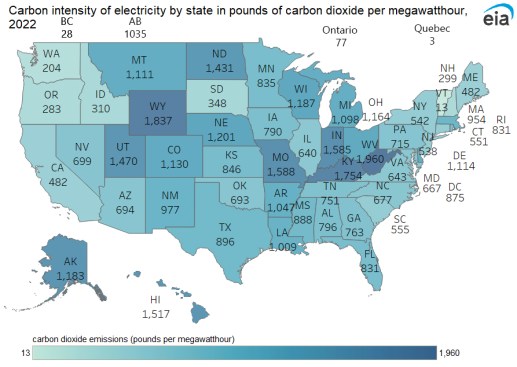

This map shows the carbon by weight emitted from every megawatt-hour of electricity generated in all U.S. states and four Canadian provinces, highlighting where efforts to decarbonize the grid are needed most.

The map above, which is based on figures from the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Power Plant Operations Report, shows the carbon intensity—the amount of CO2 emitted to produce a megawatt hour of electricity—for all U.S. states and the most populous provinces in Canada. Carbon intensity varies depending on how the electricity is generated. California, for example, generates about 53% of its electricity using renewable sources of energy, while Massachusetts generates less than 2.1% from hydro and renewables. Quebec’s carbon intensity of just 3 stands out; this is the lowest in North America owing to Quebec’s vast hydropower resources.

Concern over a carbonized grid comes into sharp focus when states and municipalities propose policies for banning fossil-fuel-burning equipment in new buildings. Pointing to a headline in the popular press, Straube referred to this as part of the “electrify everything” movement. My state, New York, has such a “gas ban” policy, which is due to take effect for new buildings seven stories and under starting December 31, 2025, and in all new buildings starting January 1, 2029. Such policies make no sense if the replacement equipment relies on carbon-intensive electricity. To be fair, it’s coupled with a New York law that requires the state to generate 70% of its electricity from renewable resources by 2030. About 38% of the state’s electricity currently comes from renewables (22% from in-state hydropower and 16% from wind and solar) so it seems fairly obvious that the “gas ban” is wildly premature.

Straube also noted that the link between decarbonizing the grid (or its opposite) and buildings goes much further than converting to heat pumps. Where building products are made has a profound impact on how we count their embodied carbon. For example, drywall made in Quebec with its electricity’s ultralow carbon intensity of 3, would have a significantly lower CO2e than drywall made in, say, Texas, where the carbon intensity is almost 900.

Last word. While I’ve only touched on part of Straube’s arguments here, I hope two things are clear: Low-carbon building is only a logical next step to building better if it’s done logically, and key to that logic is not turning our backs on energy efficiency. True, it’s going to be a steep climb before our industry makes much of a difference, but we can get started right away, even if we have to bide time until the grid improves. As a parting gift, Straube left us with some super-simple ways to begin: Don’t build if you can renovate; build smaller; build simpler; use materials and products efficiently; use materials and products with lower carbon. This last item will require care.