In many parts of the country, building codes now require air-sealing homes to a maximum 3 air changes per hour. At these levels, whole-house mechanical ventilation is extremely important. But when I travel around the country working with builders, it seems the mechanical ventilation systems being installed in new homes are often inadequate and often do not have any energy recovery. While indoor air quality is important, not having an energy recovery ventilator (ERV) can be a huge energy penalty for a homeowner. For example, a 2,500-square-foot, three-bedroom home following the ASHRAE 62.2-2016 ventilation table would require 105 cfm of fresh air ventilation. That means you have to reheat or recool a third of the air in a house every hour.

As many JLC readers know, there are three general approaches to whole-house ventilation: exhaust-only, which puts a tight house under negative pressure; supply-only, which puts the house under positive pressure; and balanced systems, which bring in as much fresh air as they exhaust stale air and impart no pressure imbalance on the house (neutral pressure). Of these, a balanced system is usually best because it doesn’t pull outdoor air (or air from a crawlspace, garage, or attic along with unwanted pollutants) into building assemblies, as a negative-pressure system can, or push moist indoor air into the building assemblies, as with a positive-pressure system. In each case, moist air from either outdoors or indoors hitting cool surfaces in those building assemblies can condense, creating moisture, mold, and decay problems.

Even with a balanced system, however, calculating the whole-house ventilation rate using the ASHRAE 62.2 standard referenced by the code is not well understood by many builders and code officials. And when code officials don’t fully understand code requirements, they tend not to inspect for them, and fewer builders are motivated to follow them. Part of what makes the standard confusing is that there are several versions with very different ventilation rates, so depending on where you build in the country and which version of the code has been adopted at the local level, the baseline ventilation rate for a continuous whole-house fan can vary.

Also, and I think this is the key point, the formulas apply to all houses and all occupants. Yes, the formula accounts for the house size and tries to account for the number of occupants, but this is indirect: The number of occupants is based on the number of bedrooms. In empty-nester homes, you could be over-ventilating and paying to recondition a lot more outside air than you need to. Or in homes with big families with more than one occupant in several bedrooms, you might be under-ventilating. Plus, occupant behaviors vary widely. In homes with lots of house plants, or firewood drying in a basement, or several teenagers taking long showers, or cooking without a range hood, there could be excessive levels of moisture and pollutants in the indoor air that are not being addressed by a ventilation system that meets code.

Smart System

For all these reasons, I was intrigued by the Broan Overture system and installed one in a new house I completed about two years ago, so I’ve had a chance to see how it works. In short, I wouldn’t want to control indoor ventilation any other way. I think builders and homeowners will love it because it automatically makes ventilation decisions based on a home’s real indoor air quality. Once set up, it requires no interaction.

For energy recovery, I selected a Broan AI Series energy recovery ventilator (ERV). On a recent day with 110°F outside temperature, it tempered the incoming fresh air to 81°F, so it recovered most of the energy I spent to cool the home.

Typically when you set up an ERV, you have to spend a lot of time fiddling with it to balance the exhaust and supply airstreams. But this Broan unit is “self-balancing.” It takes airflow measurements two times per second and automatically balances supply and exhaust airflow, making it much easier to set up as well as provide balanced air if conditions change (like a dirty filter).

However, the game-changer for me is the variety of control options the Overture system has when paired with my ERV. This system includes a number of room sensors—ones that hardwire into a two-gang electrical box or others that plug in to an existing wall outlet. The plug-in version is what you would use if you were retrofitting an existing home.

Steve Easley

The Smart Wall Control acts as a touch-screen interface for the …

The sensors monitor indoor relative humidity, total volatile organic compounds (TVOCs), carbon dioxide (CO2), indoor temperatures, and particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less (PM 2.5; a micron is 1 millionth of a meter). These tiny particles are of concern because they can move from the alveoli deep in lung tissue into the bloodstream. The sensors have LED indicators that glow green, yellow, or red to allow homeowners to understand current IAQ levels at a glance. The LED brightness is user-programmable from 100% intensity all the way down to “off.” (When I compared the Overture CO2 levels with my $175 Aranet 4 CO2 sensor, they were within 50 ppm.)

We placed the room sensors throughout the common areas of the home, as well as in bedrooms. We located them on interior walls and not in direct sunlight (the rationale is similar to how you would locate a thermostat). The kitchen range hood can also be wired to come on automatically when someone starts cooking, and there are manual timer controls in the bathrooms for local exhaust fans. The system can be set up to run in different modes: continuously or intermittently at a baseline level to meet code, or in smart mode so it will respond to the actual conditions within the home.

In smart mode, when a room sensor detects a rise in indoor concentrations of pollutants above predetermined thresholds, the system automatically activates the ERV or other connected devices, such as bath fans or the range hood in the vicinity of the activated sensor. I set mine up to run only the ERV. You can also set the system up to run intermittently to the desired minutes per hour or continuously. It even has a turbo mode to boost ventilation levels in the event of an unscheduled cooking calamity.

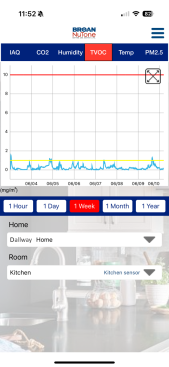

The system can also be managed through a mobile app that allows the occupants to view air-quality data in real time, track historical trends, and adjust system settings as needed. The system takes into account the outdoor air quality using the Air Quality Index (AQI; see airnow.gov) and will temporarily pause the air intake if outdoor conditions are poor, which seems to occur all too frequently during wildfire season these days.

Controlling Air Quality

A ventilation system that brings in fresh air works by diluting the concentration of pollutants in an enclosed space. While effective (assuming that the outdoor air is safe), it’s not the only way to ensure good indoor air quality. Source control (limiting the pollutants inside the home), filtration, exhausting moisture in baths and kitchens, and pressure balancing are all effective strategies that should be prioritized before leaning on dilution as a strategy for ensuring good indoor air.

I have the ERV system set up with a MERV 13 filter, which captures 75% of particles in the 1- to 3-micron range. Broan’s maximum is MERV 13. A higher MERV filter could capture a higher percentage of those particles. For example, a MERV 16 filter can capture about 95% of those particles but not without increasing static pressure in HVAC systems that can reduce airflow and put undue strain on fan motors and such. The California Energy Commission did a study to find out what happens with the highest level of filtration that you could put in an HVAC system before the static pressure started being problematic. This study showed that in terms of reducing airflow and comfort, the MERV 13 filter is at the sweet spot, capturing a high percentage of particles without imposing too much static pressure.

The Broan Overture system can be managed through a mobile app th…

The codes are slowly beginning to recognize that dilution isn’t the only way to control indoor air quality, too. The 2021 version of ASHRAE 62.2 now gives you credit for filtration. A great free calculator for determining ventilation rates for sizing a system is available at redcalc.com.

Perhaps as these technologies are more widely adopted, the codes will be able to let go of a generalized (and inherently inaccurate) basis for continuous ventilation rates altogether, and base ventilation requirements on the actual indoor conditions of each home. At this point in time, we don’t have a lot of history with how these sensors perform over time. The manufacturer told me the designed life of the CO2 sensor is 15 years; PM2.5 sensor, 8 years; VOC, 5 years; temperature and humidity, 10 years. We’ll need that long-range data and more players in the air monitor control market. But the good news is we do have the technology now.

Keep the conversation going—sign up to our newsletter for exclusive content and updates. Sign up for free