If you know your soil bearing capacity, following these practica…

Water in the Excavation

When you’re working in an area with a perched water table during the wet season, you sometimes find ground water moving into your trench. If the flow is slow enough so you can pump the water out without it flowing right back in, then that’s the best solution. You can place concrete in up to 1 inch of water — concrete is 2 1/2 times heavier than water, and it will displace the water. You might want to thicken the footings in that case, because the bottom of the concrete may absorb some water and be a little weaker than normal.

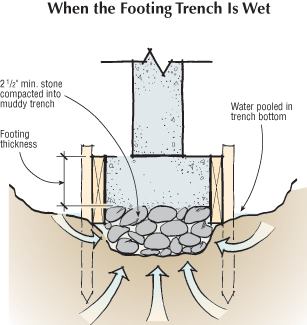

But if the soil is loose and porous, and water and soil keep coming back into the trench as you pump the water out, use large aggregate to build up the trench. For this, large stone or cobbles — 2 1/2-inch- or 3-inch-diameter rock — are best.

When you form the footings, place enough large stone into the wet, mucky zone to get up above the water table. Compact the stone down into the mud, then pour your footing. The large aggregate allows the muck to fill into the pore space, but as long as all the pieces of stone are in contact with each other, the stone can still transfer the load.

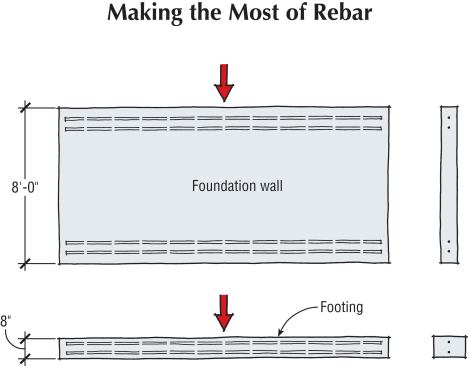

If the stone is piled so high in the forms that your footing becomes too thin (less than 4 inches thick), place transverse rebar to reinforce it (be sure that the footings are thick enough to cover the steel by at least 3 inches).

Changes in Elevation

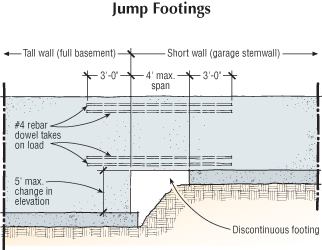

It’s pretty common for a short wall to tie into a tall wall, especially in the North, where most houses have full basements but garages just have short frost walls. The code calls for continuous footings at all points. But that part of the code dates from the days when foundations were made mostly with concrete block, not poured concrete. Masonry foundation walls have no real spanning capability, so they have to be stepped down when elevations change.

Concrete walls, on the other hand, can be reinforced with steel to span openings. That means the footings can be discontinuous, jumping from the 4-foot to the 8-foot or 9-foot elevation. The shorter wall can span the distance.

The concrete has to be appropriately reinforced. A typical house situation, where a 4-foot garage frost wall has to span 4 feet or less and tie into the main foundation, calls for two #4 bars at the top of the wall and two #4 bars at the bottom. The steel has to extend 3 feet into the main wall and 3 feet into the shorter wall beyond the point where the footing starts.

For this detail, the footings are formed and cast as usual. When you form the walls, the bottom of the forms must be capped with a piece of wood where the forms pass over empty space. In termite country, that wood must be stripped when the forms come off.

Brent Anderson is a consulting engineer and concrete contractor who serves on the American Concrete Institute Committee 332, Residential Concrete.