Panelizing Houses – Continued

It’s important to remember, though, that this machine’s capabilities can’t be fully realized without good software to run it. As my shop foreman says, “Without the software, it’s no better than a $25,000 tape measure.”

Subcomponent nailer. The second station on the line is the subcomponent nailer, which allows one operator to assemble headers, corners, partition lead-ins, and other framing details before the panel reaches the framing table. Our homes generally have standard window and door sizes to make it easier to assemble and inventory subcomponents.

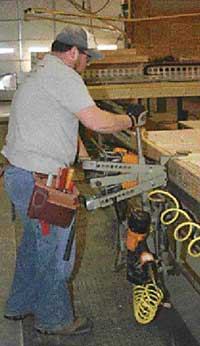

Framing table. Next in line is the framing table; this is where the preassembled subcomponents and studs are automatically placed and clamped within the top and bottom plates. A man on each side of the table rolls a carriage holding double pneumatic nail guns; he fastens the plates to the studs and subcomponents as he goes.

When this operation is completed, the wall panel is rolled to the squaring table and sheathing bridge.

Squaring table. Here, the panel is instantly squared to within 1/32 inch and the sheathing is applied and stapled automatically. Once the sheathing is tacked in place, we cut out the windows and door openings with a two-man router. In our shop, the sheathing bridge is manually positioned over the studs and a pneumatic nailer travels back and forth across the bridge, automatically fastening the sheathing.

Then the panel is lifted off the table by electric hoist, and stacked and banded for shipment.

How Much It All Costs

The assembly-line equipment accounts for the biggest capital investment, but there are many other smaller purchases that add up, too. For example, all the equipment in the line is air-driven, so a high-volume air compressor is essential.

We also precut floor joists and rafters using a 7 1/2-hp power-feed radial-arm saw, and there are several cutting stations requiring top-quality miter saws. Plus we have forklifts, trucks, rolling tables, benches, and other small equipment.

So, what’s the bottom line? Aside from the price of the facility itself — which, of course, varies by location — costs for the equipment, software, and installation needed for a new semiautomatic operation run in the range of $250,000.

This is a significant expense, but it provides an efficiency that can’t be touched with on-site building. Moreover, it’s far less than the million or more dollars that can be spent on a fully automated plant. With sufficient volume, this cost amortized over several years makes sense, given the increased efficiency.

Our company can produce a full set of plans — complete with shop drawings — and turn out a custom 2,500-square-foot house with panelized and sheathed walls and precut floors and rafters in about 60 man-hours. A skilled framing crew can have a simple design erected and dried-in within one week; designs that are more complex may take another week.

More Than Just a Shell

While framing is an important element of off-site building, our company has introduced another level of off-site efficiency with our prebuilt architectural details. We routinely build front entrances, cornices, pilasters, and Greek Revival corners in our shop so that they can be quickly installed in the field.

Again, producing these pieces requires sophisticated drafting capabilities. All of our architectural details are drawn in minute detail, and we are able to quickly access the appropriate designs in our large library stored in BuildersCAD.

We also prebuild many of the less complex exterior trim pieces because we can do it faster and better in our shop than in the field. We rabbet the fascia, prerip all soffit pieces, apply crown mold to fascia, and prebuild returns and corner boards.

Buying Materials

We buy most of our material from one supplier. Since full units of framing lumber are the norm and save time and handling at the lumberyard, we get lower prices. We use so much molding our supplier has made special arrangements with the molding producer for factory priming of profiles not commonly available with a primed finish.

We have to buy 5,000 or 10,000 feet at a time, but since our facility has plenty of storage, this isn’t a problem.

Myths and Misconceptions

One of the myths about off-site building is that customization is impossible. While it’s true that our company has a standard catalog of colonial reproduction homes, most of our builders and homeowners either customize these plans or start from scratch with our design department.

Once the design is finalized, we price the panelized shell package with all windows, doors, trim, roofing, and siding, and we also price a separate interior package that includes stairs, doors, flooring, trim, and cabinetry. Exterior home packages generally range in price from about $45,000 to $150,000.

Another common myth is that off-site construction is of lower quality than site-built. I don’t think that’s true.

Our plans are scrutinized by the designer and production team, so any quirks or problems are addressed well ahead of time; and the homes are constructed in a controlled environment with greater oversight than most site-built houses receive.

Considering the advances that have been made in the house panelization industry, any builders looking to increase volume and overall efficiency should consider setting up at least a small off-site building program so they can remain productive when the weather is bad.

Even though our new facility could probably turn out hundreds of homes a year, we’ve chosen to stay small because my staff and I want to be home builders — not assembly-line workers.

Mike Connor is a home builder in Middlebury, Vt.