Glenn Mathewson

Landscaping designs and decking without gaps can drastically aff…

Wood can rot—there’s no argument about that. But there is some confusion about when building codes require you to mitigate rot, specifically in deck construction. Codes recognize that wood simply getting wet does not cause rot. The natural world is constantly wetting and drying, and as long as both are occurring in cycles, all is good. But if wood can’t dry out—because of high humidity and heavy precipitation, or construction details that trap moisture—decay can become a problem.

The 18-Inch Rule

Moisture content is always seeking equilibrium, moving from wet to dry. An evening rainstorm may saturate the area below a deck, but in many parts of the country the ground will be dry by the next nightfall. This is why deck joists—despite being exposed to the elements—often fare better than floor joists that are located above a traditional vented crawlspace with an exposed earth floor. Though the crawlspace is sheltered from precipitation, its earth floor is subject to moisture escaping the adjacent rain-soaked earth outside.

To provide for airflow to help dry out ventilated crawlspaces, codes require them to have one square foot of openings per 150 square feet of under-floor area, and one opening within 3 feet of every corner. A 600-square-foot crawlspace with only 4 square feet of ventilation openings would therefore meet code; clog those vents with insect debris and paint, and the moisture has nowhere to go. The closer the joists are to the earth, the worse the drying conditions are.

This is the origin of the requirement that lumber used for framing that’s closer than 18 inches to the ground must be naturally durable or preservative-treated. This provision (2012 IRC, R317.1) applies to under-floor areas that are within the periphery of the building foundation, and not necessarily to decks.

-

Deck and Railing Skills Workbook

No one can afford a deck failure. Focus your crews on safe and durable deck building with JLC’s Deck and Railing Skills Workbook.

Unlike crawlspaces, decks typically have plenty of airflow—at the edges and through gaps between deck boards. However, the amount of ventilation can vary considerably. Is there vegetation adjacent to the deck? Is there a solid skirting around the deck, from decking to grade? What if that skirt is an open lattice? Some manufacturers of porch-style tongue-and-groove decking require ventilation below the deck to compensate for the lack of airflow through the solid decking surface.

Proximity to the ground isn’t the only concern; precipitation is another. Conventional wood-frame construction creates many interfaces where lumber contacts lumber, with small gaps and cracks in the joints that don’t dry easily. Spaces between the joists and the decking, between multiple beam plies, and at notches and tops of posts are all subject to significant wetting and inhibited drying.

The Inspector Rules

In most cases, construction that’s affected by differing climatic conditions—think snow loads, wind speed, and termite populations—is not addressed uniformly in codes. This is true of decks, for which wetting and drying potential varies widely from one region of the country to another. Section R317.1.3 recognizes this variety and allows the local building official to determine which exterior structural elements must be decay resistant; different regions, then, may have different requirements, based on local conditions and the manner of construction:

2012 IRC, R317.1.3 Geographical areas. In geographical areas where experience has demonstrated a specific need, approved naturally durable or pressure-preservative-treated wood shall be used for those portions of wood members that form the structural supports of buildings, balconies, porches or similar permanent building appurtenances when those members are exposed to the weather without adequate protection from a roof, eave, overhang or other covering that would prevent moisture or water accumulation on the surface or at joints between members. Depending on local experience, such members may include:

1) Horizontal members such as girders, joists and decking

2) Vertical members such as posts, poles and columns.

3) Both horizontal and vertical members.

While this section speaks to decks, it isn’t very specific. Many building officials may not even be aware that the decision is theirs, and may simply fall back on the 18-inch rule mentioned above. Inconvenient as it may be, contractors must ask the local building official what’s required. The best approach is to recognize that code is a minimum standard and to build with appropriate decay-resistant lumber even when not required by code.

By the way, the same provision (2009 IRC, R502.2.2) that introduced deck builders to the controversial IRC lateral-load connection detail was the first one to require preservative-treated deck ledgers. (In the 2012 IRC, R502.2.2 was moved to R507.2, at the end of chapter 5.) Looking ahead, a number of new deck-specific details will be included in the 2015 IRC (see “2015 Deck Code Update,”Jul/Aug 2013).

Decay Resistance

With the withdrawal in 2003 of CCA lumber from most residential applications, ACQ-treated lumber quickly became the industry standard. But subsequent problems with hardware corrosion created a need for other options, and today there are many conventional and alternative products on the market for decay-resistant lumber, though much of it is for decking only (see “Cooked, Pickled, and Glass-Infused Decking Nov 2011).

The IRC references the American Wood Preservers Association standard U1 for acceptable treated-lumber methods, retention levels, and exposure conditions (awpa.com/standards/U1excerpt.pdf). The most common products used for decks from this list are ACQ and PTI. Micronized copper quat (MCQ) is also relatively common but must be approved as an alternative.

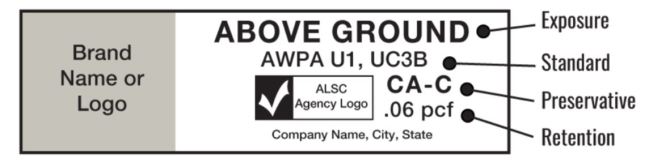

While the standard provides the nitty-gritty details, in practice it’s the material’s identification tag that’s important to inspectors (see image below). The IRC requires a tag with seven items of information on each stick of treated lumber (though there are exceptions for small sizes). The end use the product was treated for is generally the target of inspection.

The ICC codes reference American Wood Protection Association (AWPA) standards for treated wood so one of the first things an inspector will look for on the end tag is "AWPA" and the applicable standard, usually "U1." The tag should also identify the preservative type and amount of preservative retained in the wood (retention), as well as the AWPA Use Category (in this case, the use category is UC3B – "Exterior Above Ground, Uncoated or Poor Water Runoff").

Another way to satisfy the requirement for decay-resistant lumber is to use wood that is “naturally durable.” The IRC lists four species—redwood, cedar, black walnut, and black locust—with limitations on the amount of decay-prone sapwood permitted.

Ground Contact

When wood is in contact with the ground, its drying potential is dramatically reduced. Any time lumber is embedded in the earth, in concrete in contact with the earth, or in concrete exposed to the weather, the IRC requires the lumber to be preservative-treated with higher retention levels and labeled specifically for “ground contact” use. No naturally durable materials are permitted, unless they are also treated. 4×4 and 6×6 posts are commonly rated for ground contact, but this isn’t necessarily the case for 2×12 stock for stair stringers. The IRC doesn’t strictly require a ground-contact rating for lumber that is only in contact with (rather than embedded in) concrete, but your building inspector might.

Field Treatment

Since 2006, the IRC has required field treatment of all cut ends and bored holes in treated lumber, in accordance with AWPA Standard M4. This isn’t standard practice in the decking industry as far as I can tell, largely because the details are in M4 rather than in the IRC. M4 specifies copper naphthenate for exterior use and borates for interiors, and distinguishes between species with thin and thick sapwood.

Sapwood is more susceptible to rot than heartwood is, but it absorbs preservatives much more readily. Thus M4 generally doesn’t specify field treatment for species with thick sapwood (such as pine) for profiles measuring 6 inches or less in above-grade applications. If a notch in a post reveals inner tree rings, though, it’s a good idea to field-treat it.

Douglas fir, on the other hand, has thin sapwood and does not take treatment well, which is why it’s commonly incised prior to treatment. Inside a cut end, it’s easy to see the minimal penetration of treatment and the need for additional preservative. As a consequence, M4 specifies field treatment for all cuts in treated Douglas fir and hem-fir, whether or not the wood is in ground-contact.

For ground-contact applications, M4 specifies field treatment for all cuts. In deck construction, water trapped in above-ground joints—such as the top of a support post or the end of a joist—can create the equivalent of a ground-contact situation. So, it’s a good idea to think of the code as only a minimum standard and treat any cut end located in a joint where drying is inhibited.

This article originally appeared in JLC’s sister publication Professional Deck Builder.

![Bearing “on” concrete vs. “in” concrete makes a difference in whether material must be ground contact rated or not. In this example, placing the lumber in a post base with a standoff would have been a better choice.]](https://jlconline.stg.zonda.onl/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/06/decay-resistance-60-tcm122-2141899.jpg?w=489)