The physicality of the trades is a point of pride for most contractors. We mark out the day by what we moved, the number of steps we took, and the hours worked as much as the money earned.

When I started working construction, I was struck by how broken the bodies of the older men I was learning from were: hips ready for replacement, knees shot, and backs doubled over from the mileage of many years of work.

Mark Clement’s Jobsite Workout

Carpentry and construction work loads the body asymmetrically. Purposeful exercise, on the other hand, is about symmetrical loading and it flips different switches in your body. Here are a few of the exercises that have worked for me during my career behind the saw.

Read more.

If you are getting your 10,000 steps in before lunch, moving heavy materials around jobsites, and perhaps climbing through roof trusses like an acrobat with a toolbelt, you may believe you are getting all the fitness training you need. The issue is that those are deconstructive activities, which are a stress on the body, and too much stress can cause problems down the line. A fitness routine, however, is a constructive activity, which prepares and maintains your body to handle stress.

According to OSHA, 3.8 out of 100 people working in construction jobs will suffer from repetitive strain injuries during their career. With more than 8 million people employed in the industry, 6 million of those directly in the field, that is a lot of people who want to work but are unable to. This should not be taken as a lecture on what we are doing wrong. We take safety much more seriously than when I started 20 plus years ago, and the declining number of deaths and serious injury back that. Our next goal should be to help ourselves in other ways.

While working on this article, I spoke with Mark Clement, a JLC contributing editor and former editor of Tools of the Trade. (see sidebar link above) He is serious about body care in the trades and helped me form the idea of constructive and deconstructive activities. He also pointed out that the habits around fitness and body maintenance are not built-in for most people. If you didn’t play organized sports growing up or experience the direct relationship between good diet and exercise and performance at a task some other way, why would you be thinking about body health and how it affects your workday? Just as you created habits to efficiently frame a house or shingle a roof, you can learn and form habits to care for your body.

We learn by paying attention to results. So pay attention to how you feel. If your back feels stiff most days, try a stretch a few times and see if that helps. If your energy crashes by the afternoon, try a different lunch or an afternoon snack to carry you through. By listening to your body, you can form a habit that improves your outcome.

Your body is your most important tool. All the tools in the truck and years of experience on the job will not get the work done if you can’t move. If you want a long-term career, not just a short-term job, you will need to create habits to support that goal.

My Daily Stretch

I do not have a background in sports or fitness, so the idea of listening to my body did not come naturally. As the aches started to build up and affect my production, though, I had to pay attention. What I share here is not a full wellness routine—that would be a much longer article and not my expertise—but one that works for me. I took each of the main pinch points that my body had and formed a habit that helped counter each one. Your issues may be different, but the idea, much like finding a more efficient way to organize your work, is to see a problem and find a way to deal with it. The photos on these pages show the stretches I do daily to deal with my particular problems. I describe them in a bit more detail below.

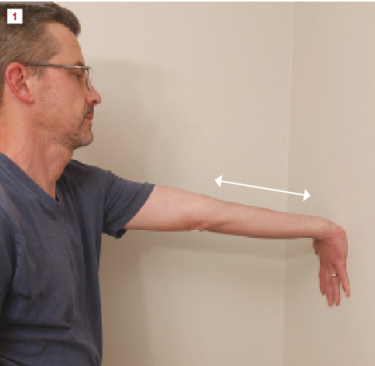

Forearms. This stretch helps prevent my forearms from tightening up so much that holding tools and moving materials cause pain and numbness right to my finger tips. I can also do this stretch in the van on the steering wheel or dashboard while in traffic to release tension.

Push your palm flat on a wall or table and extend your arm straight. Hold for 10 and switch arms.

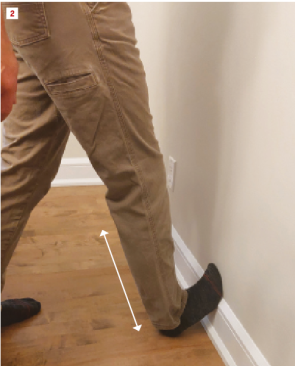

Calves. My muscles used to get so tight from working on a ladder or being on my knees that they would fall asleep and go numb when I went to bed. By putting my foot on a wall and slowly bending my leg, I could prevent a blinding charley horse in the middle of the night.

For the calf stretch, place your foot against the wall and straighten your leg. Hold position for 10, and then release slowly and switch to the other leg (2). Both this and the forearm stretch should be repeated three or four times.

Back. I am not the largest of men, so my back on this slim frame takes a lot of abuse. For this ache, reaching down and touching my toes gives me the mobility I need. A few slow and full movements of this stretch with my arms extended up to the ceiling and then down to the floor are usually enough to work out any built-up knots.

For the back stretch, when you touch your toes (or get as close as you can), try to keep your legs straight. When you release, slowly raise your arms above your head.

Neck. According to my massage therapist, everybody keeps their stress in a particular part of their body. For me, it’s my neck; the stretch shown is one I was taught to use to work that tension out. Sit up straight in a chair, grab the chair with one hand, and lean over in the opposite direction, keeping the other arm loose. Hold this to a count of 10 and then repeat for the other side.

When I do the neck stretch, I hold the chair on the stretched side and leave the arm loose on the side I lean toward. Hold for 10, release, and repeat (4). Do all of these motions slowly, breathing as you go. If you feel a sharp pain, stop right away and adjust until the pain is not present.

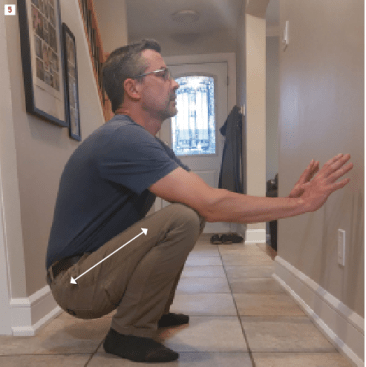

Hips and lower-body muscles. My hips and parts of my upper legs started to complain—it’s fun getting old—so I now do a squat that has helped. It is supposed to open up the pelvic area, work major lower body muscles, and improve balance, as a bonus. With your feet flat on the floor, shoulder width apart, lower yourself to the floor while keeping your back straight. Then rise up slowly and repeat. (Don’t forget to breathe.) At first, you may need a wall in front of you for support but, after some time, I was able to do this without tipping over.

While you are doing the squat, you will feel the muscles in your legs, glutes, and back working. Try to keep your arms straight out and your back in a vertical line, too. I am not there yet all of the time, but practice will lead to better result.

These exercises have helped me, but your pain points may not be the same as mine. Pay attention to your discomfort and then create a habit that deals with it. Do your research and ask trusted people for advice. Consult your physician. Just as you learned better ways to hang a door, try different things that will help your body work better and feel better as you age. You have time to start habits that will extend the length and quality of both your career and your life outside of it.

Keep the conversation going—sign up to our newsletter for exclusive content and updates. Sign up for free