I began working with building officials when I was 16 or 17 years old, so I’ve been involved with building departments for more than half of my life. If you include my dad’s experience, which I learned from, you could say I’ve been doing this since the first part of the 1970s.

Over time, my company has worked with a number of authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) and many building inspectors. We have had struggles with a few inspectors, but with most of them, we’ve had excellent relationships. Hopefully, some of the lessons I’ve learned will help you in your building endeavors.

I’ll break this down into three main parts: what the inspector’s job is, what my company does to prepare for an inspection, and what we do when we disagree with an inspector.

Thumbs up. The author (right) with his local building inspector and a completed inspection card.

Understand the Inspector’s Job

A refrain that’s currently popular in our industry goes something like this: “A house built to code is the worst built home that is legally allowable.” I couldn’t disagree more. While the building code isn’t perfect, I have yet to find a section of the code that is “stupid.” If we view the code as helping to ensure that a home reduces the likelihood of occupant death or injury, it meets the purpose nicely.

Think of code officials like public health officials. A code official’s job is to ensure safety. For the structural code, that means ensuring that a building doesn’t fall down on the occupants or occupants don’t fall down unsafe stairs or off decks and balconies. Then there’s the fire code: A building shouldn’t catch fire easily and if it does catch fire, the occupants must be able to escape safely. The plumbing code is all about sanitation and health, so occupants have clean water and can get rid of human waste, and the waste doesn’t mix with the clean drinking water. And we have mechanical codes so that gas leaks and combustion gases don’t kill occupants, and so on. Of course, if a code has been adopted where we are building, we are bound by law to that code. Some of us feel a strong moral and ethical binding to build to the code.

While the building code isn’t perfect, I have yet to find a section of the code that is “stupid.” If we view the code as helping to ensure that a home reduces the likelihood of occupant death or injury, it meets the purpose nicely.

The building inspector’s job is to ensure the house is built to code and, depending on where you are, ensure it is built to plan. I’ve found that most building inspectors have certain items that they are most focused on. Our area is in a high seismic design category, so inspectors are not likely to double-check cabinet layout dimensions, but they will check the rebar, hold-downs, and anchors. At final inspection, they will use a gas detector and check for leaks at gas appliances. They will also check for functionality of smoke detectors. (They inspect plenty of other things, too; this is just a sampling.)

The point is, focusing on why the inspector is inspecting may temper somewhat the animosity some builders feel for the inspection process. Structural inspections are, to a reasonable degree, intended to prevent catastrophic failure or death to the occupants.

What to Do for a Building Inspection

There are things we do to improve our chances of having a successful inspection. First, we try to schedule inspections early enough to prevent panic. When I first started in this business, if we had a concrete pour, we could call in at 3 p.m. the day before the pour, ask for a morning inspection for concrete, get the inspection, place the concrete, and Bob’s your uncle. Now, it could be seven days or more after calling in an inspection before the inspector can get to the site. Then again, we might be able to call day-of and be given a window of time for an inspection. But even if they give us a window, it may change; we can never plan the exact time for the arrival of an inspector. This means that, for high-stakes inspections—like the placement of concrete referred to above—we cannot fail. We need to be dialed in because if we fail, it is 100% critical path. No dominoes fall without the foundation.

For other inspections, we have more flexibility. Say the plumber forgot to put a stud shoe on. In our area, the inspectors will just check it with a later inspection. They will also give us the OK to insulate as long as any corrections we need to make will be inspectable. We’re able to do more with photos and videos for certain things, but communication is key. If remote-style inspections are going to be a part of the process, we try to find out exactly what the inspector wants to see. For example, if we’re installing underslab insulation, we make sure photos are taken of the insulation R-value.

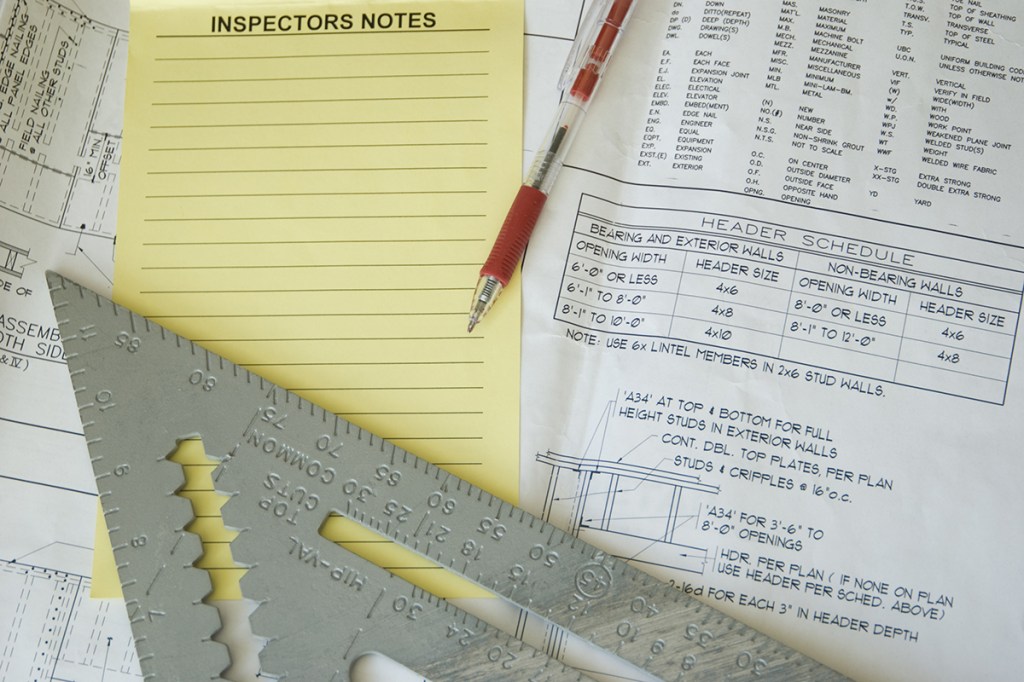

Having the plans and permit card organized is helpful too. We don’t get fancy: I have a bunch of folders from Staples that I keep everything in. I get the permit set scanned as well as copied and laminated. In general, the permit set is only for the inspector, not to build from. Some AHJs may require permits and plans to be posted and present on-site at all times, so make sure you know what’s needed where you’re building. Some builders have job offices or command centers that stay on a project from start to finish, but we don’t. In our case, we deal with the Pacific Northwest rain, and we build from clearing to final. We just make sure that the permit and plans are on-site for any scheduled inspections.

Another tip is to have the jobsite tidy and clean. If you went to a doctor’s office and the place looked like a bomb went off, you might be inclined to think that this professional doesn’t have his house in order. The same is true for a jobsite. It doesn’t have to be spotless—no need to go overboard. But if it is broom-swept and piles are tidy, the inspector has less mental “noise” to contend with.

In construction, much attention is paid to the technical side of things, but we should also focus on honing our “soft skills.” Listening to an inspector’s questions, responding respectfully, and having good questions all help build a strong working relationship.

Sites should also be safe for the inspector to visit. Passive fall protection (like guards and rails) and paths of travel should be given due attention.

Usually either my brother or I will be on-site for an inspection. Sometimes we wait around for hours, but failing an inspection is far more likely if we don’t have a company representative on-site. All of our primary employees are competent to meet with the building inspector. However, some employees have more of a core competency than others. Also, some of our employees may be able to care for an item during the inspection more readily than others. For example, my brother is our lead for structural concrete and framing. Having him walk through on a foundation or framing inspection is helpful. When it comes to a final inspection, my brother-in-law, who also works for us, is a good person to walk through with the inspector because he is adept at punch list items.

Sometimes I walk with the inspector, sometimes I don’t. There is a balance between speaking too much and too little. Being affable and showing that I’m trying to connect on a human level are things I’ve found helpful. It isn’t about manipulating the inspector; rather, it is about demonstrating that we’re shooting for the same goal. This goes back to respecting the code and the inspector.

In construction, much attention is paid to the technical side of things, but we should also focus on honing our “soft skills.” Listening to an inspector’s questions, responding respectfully, and having good questions all help build a strong working relationship. There may be things we did that an inspector doesn’t understand but will agree with once we provide a clear explanation. We should also be willing to acknowledge when something is wrong and then humbly correct it.

When We Disagree With an Inspector

Sometimes, we don’t see eye to eye with an inspector. Not all situations are the same, and each builder, project manager, or owner needs to navigate them individually. Some builders will tend to do what an inspector says, and there are at least two reasons for that: Some do it to keep on schedule; others may be intimidated by the building code.

To stay on schedule, some builders may feel it’s best to lose the battle and win the war, so to speak. In other words, they are facing pressure related to the project and the cost/benefit of getting into an argument tilts toward the benefit of moving on.

Other builders may not have comfort dealing with the building code, and this is perfectly reasonable. Many builders and subcontractors have a predilection to building with their hands, creating something tangible, and the highly specific language and technical organization of the code do not come naturally. Because building inspectors work with the code all the time, it is natural for builders to default to the position that an inspector is right. However, following that logic, you could say that builders always build right because they do that for hours every week.

We do need to respect building inspectors for their broad knowledge of the building code. At the same time, we should recognize that they aren’t infallible. A good builder should seek to understand the building code as well as its intent. When we do this, we can engage in a productive dialogue with a building inspector in an educated, respectful manner.

We do need to respect building inspectors for their broad knowledge of the building code. At the same time, we should recognize that they aren’t infallible. A good builder should seek to understand the building code as well as its intent. When we do this, we can engage in a productive dialogue with a building inspector in an educated, respectful manner. This is the same thing we want from the building inspector. He or she will know about construction and how it works, but we want them to respect us for the many hours of every week we do our jobs, too.

An Example of Productive Disagreement

I had a recent experience with a building inspector having to do with fireblocking. I got into Chapter 3 of the IRC (International Residential Code) regarding building planning and felt the inspector was wrong, but I was also willing to accept the possibility I was missing something. So I emailed him, and he stuck to his guns. But I wasn’t sure he understood where I was coming from. So I called and left him a detailed voicemail (his salutation encouraged that). I didn’t hear anything, so I emailed him again. He acknowledged that he hadn’t had time to review it, but he still stuck to his position. However, we’ve worked together a lot, so he graciously gave me the name of another person at his office and the state code council as further contacts if I wanted to pursue the question. So, I typed up a letter, sent it to his co-worker, cc’d him, and before long received a response that my understanding of the code was correct.

Is going to that level wise? It depends. This inspector and I get along well. But if I had let this matter pass, our team would have lost time having to take care of it. And not just once. We build a lot in his jurisdiction, so we would potentially have to multiply that time by every fireblock in every house where this would have applied. I’d like to add that I wasn’t all wound up about it; keeping emotion out of it allows an inspector to hear what we’re saying with a clearer head.

Consider It a Skill

If you work in an area with building inspectors, strive to become skilled at working with them, just as you work at being skilled in construction. It is a necessary part of the process. When we respect the code, empathize with inspectors, prepare well for an inspection, comport ourselves professionally during an inspection, and respectfully engage in productive dialogue when there is a disagreement over the code, we justify our being called “professional builders.”