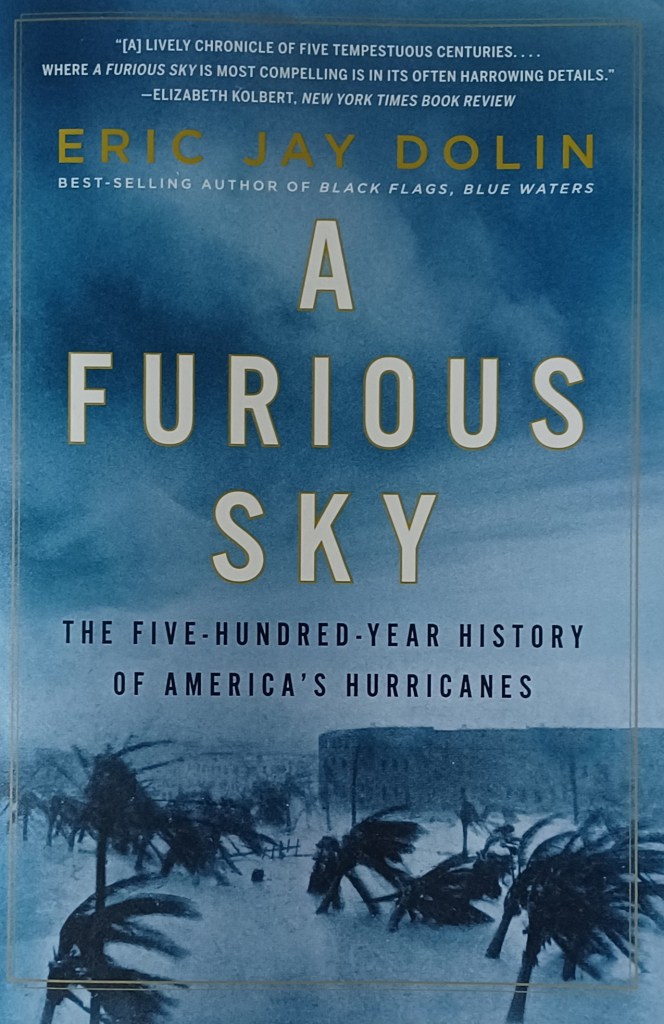

Eric Jay Dolin’s 500-year history of the hurricanes that have battered the United States is a brutal read. A Furious Sky, which was published in 2020, chronicles the most consequential impacts of more than a thousand storms that have swept into and across the country, beginning with those Christopher Columbus predicted and was able to dodge (having learned the signs from the indigenous Taíno of the Caribbean islands) to Hurricane Imelda in 2019.

“Coursing through the centuries like brawlers bobbing and weaving and slugging anyone and anything that stands in their way, hurricanes have left an indelible mark on American history,” Dolin writes. “Since 1980, they have accounted for roughly 50 percent of the cost of all natural disasters in the United States that exceed $1 billion in damage. And going back to the late 1800s, hurricanes have killed nearly 30,000 people.”

Perhaps we’ve become inured to such a number of deaths after the 298,000 killed during World War II, or the 620,000 during the Civil War, or the astonishing 1.03 million (at the time of this writing) U.S. deaths from COVID. But Dolin’s accounts are painted in painful detail, stripping away any indifference we might hold onto as he reveals the physical and emotional turmoil inflicted on families and communities by these storms. After all, just one death can have a profound impact on those left behind, and it is all the more intense when the circumstances of that death play out like a nightmare.

‘… hurricanes have the humbling ability to strip away the trappings of modern society and return us, if only temporarily, to a time when electricity, clean water, sanitation and even a roof over one’s head were unimaginable luxuries.’

While his retellings of eyewitness accounts during storms are truly terrifying, it’s the description of the storms’ aftermaths, in duration and severity, I find most dreadful. “Even as the hurricane has passed, the water left behind remains a serious hazard,” Dolin explains. “By destroying what humans have built, hurricanes liberate a host of toxins into the environment … Regardless of the category and the amount of water that surges in or rains down, hurricanes have the humbling ability to strip away the trappings of modern society and return us, if only temporarily, to a time when electricity, clean water, sanitation and even a roof over one’s head were unimaginable luxuries. By leaving behind the detritus of civilization—mangled buildings and torn landscapes—hurricanes redefine reality and fracture people’s lives.”

Dolin delivers examples of redefined reality and fractured lives in spades, while weaving a diverse number of themes, including the storms’ effect on war, governance, and the economy, together with portraits of charity and resilience to mirror all the devastation. Most intriguing to me, though, is the continuous thread he follows in our ability to predict, analyze, and understand the development of storms and influence the public, which has been a significant factor in the number of lives upended by each event. While Columbus listened to the Taíno and saved his ships, he was also accused of witchcraft, and not surprisingly, little of the indigenous knowledge endured. Radio brought some ability to track storms, but only early on in a storm’s development, as the reports were relayed by ships that alerted other ships that moved out of the way, making forecasting of where a storm might land more difficult as the storms grew. Airplanes that could fly into storms helped, though not without great peril to pilots and navigators. It wasn’t until the development of weather satellites and radar improved efforts to monitor the progress of storms in real time that predictions improved.

Convincing the public to take storm warnings seriously took a little longer, as predictions had previously been so unreliable. It wasn’t until 1961 that a local TV news director from Houston named Dan Rather decided to superimpose the map of Texas over a radar image of Hurricane Carla that the public got a visual on the magnitude of a Category 5 hurricane. His reporting, and subsequent mass evacuation of Galveston, is credited for saving countless lives. Thereafter, weather reporting was transformed, and with that came another problem: sensationalism and overreporting. E.B. White summed up the problem best in 1954, Dolin reports: “‘… we are still trying to balance the role of media in informing us about impending hurricanes, while simultaneously not allowing their reports to become so over the top that we start ignoring them altogether, by virtue of their repetitive and alarmist nature. It is a fine line that separates effective reporting from hype that numbs the senses.’”