Environmental Health Watch

All of the houses in the HUD-sponsored technical study were buil…

Ventilation vs. comfort. The original idea of delivering fresh air directly to the bedrooms proved to be problematic in our DER mini-split houses. When the bedroom doors were closed, cool air delivered to the rooms in winter led to complaints of discomfort. We used “bath fans” in the common space near the mini-splits to increase circulation of conditioned air to the bedrooms, but it was not enough to offset the chilling effect of the ERV air.

To correct this, we disconnected the fresh-air supply to the bedrooms, allowing it to dump into the basement instead. This way, the cooler fresh air mixes with backup heat at the point when the heat pump becomes less efficient. In other cases, we diverted the fresh-air supply, dumping it out under or near the mini-split heat source to be mixed there. (In the ducted houses this was not an issue, since the fresh air blows into the cold-air return, where it is further filtered, heated, and mixed with the house air.)

With a more efficient ERV, incoming air temperatures would not be quite as cold. For this project, we were trying to find the balance between price and efficiency and locally available equipment. In the future, however, we would likely use a more efficient ERV, with simplified and reduced ductwork that might balance out the upgrade cost.

Also, occupant education and property management efforts must include some attention to maintenance of the ERV system. If filters are not cleaned, the potential exists for reduced airflow and functionality. While the need to clean filters on an ERV is less frequent than with a typical furnace, the need for ensuring fresh air is much more important in a DER, or otherwise tight house.

Dependence on mechanical ventilation. In a very tight home, occupants depend on mechanical ventilation to deliver fresh air and remove contaminants, moisture, and odors. When ventilation stops working, IAQ suffers. The need to ensure that the ventilation stays on in our tight DERs presented some challenges that we are still evaluating. For example, during a few of our home visits, we discovered some instances where the ERV system was not running. In one case, when addressing a complaint about a “stuffy” house, we found that the ERV unit was unplugged. In another, the occupant suggested that things seemed different since she cleaned her ERV filter; in fact, the ERV was off. As it turned out, two of the six ERV units we installed require that you hit the reset button after opening the ERV cabinet, but we didn’t know about this and didn’t warn the occupant. These experiences are relevant for any project with an increased focus on airtightness.

Occupant control. The ASHRAE 62.2 standard makes ventilation automatic, taking it out of the hands of the occupant. This has been determined to be a safe approach toward ensuring good IAQ, although there are challenges in that the ventilation rate is certainly too low when there is a house full of people smoking or cooking, and it is probably too high when no one is home. It would be nice to give the occupants more control over their ventilation, if we could trust that they would use it “right.” It would be even better if the ventilation controls were based on IAQ levels (for example, if measured CO2 and VOC levels in the home would turn on the ventilation), with boost switches provided for cooking, showering, smoking, and so on.

Demand-controlled ventilation has long been used in commercial buildings, but now there are some residential systems being developed. Ventilation does consume a lot of energy, and that is something to be considered as part of an overall energy reduction strategy. Under-ventilation can be dangerous, but over-ventilation can wipe out all of the energy savings gained from an airtight, super-insulated shell. For now, ASHRAE 62.2 is the accepted balance between the two.

Cost Considerations

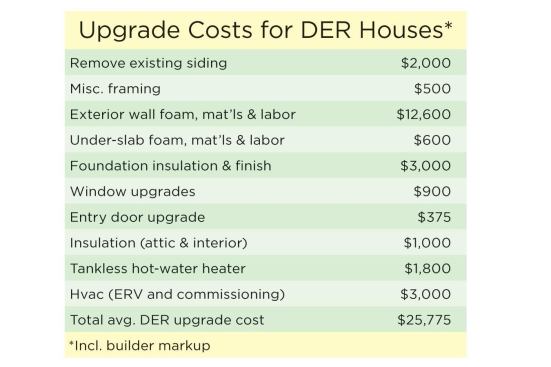

These DER upgrades added nearly $26,000 to what was already a substantial gut renovation. This added cost would be a problem for most market-rate builders and developers, since the sales price of a house is based on its appraisal, which is based on comparable sales. Comparable sales are hard to find in a depressed housing market, so spending this much extra could be considered “over-improvement” from a short-term investment standpoint. For a developer without subsidy, it is impossible to stay in business if costs are higher than sales prices.

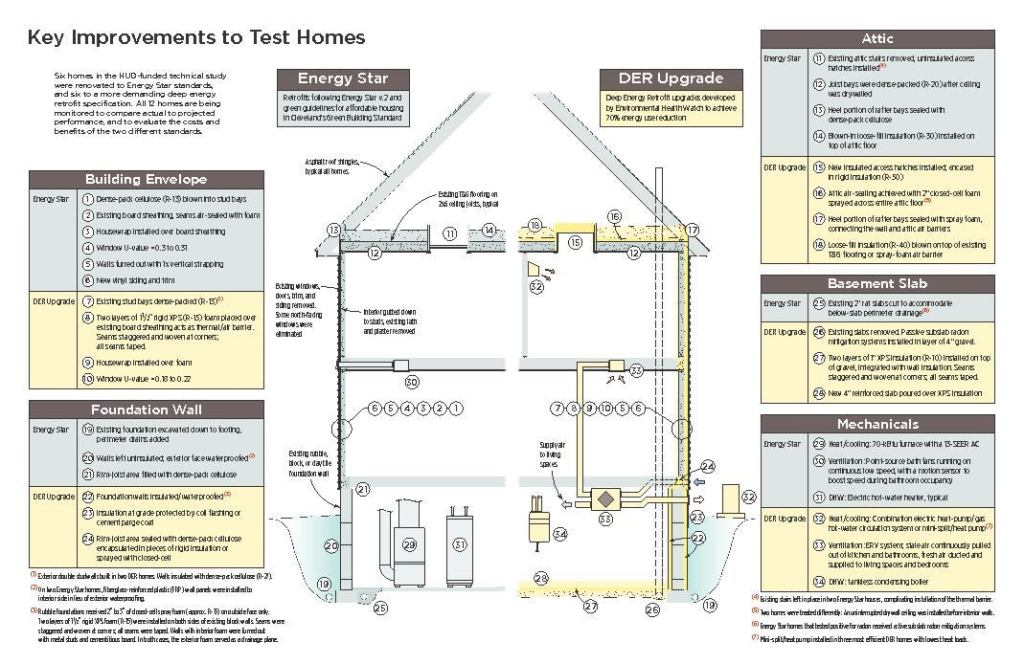

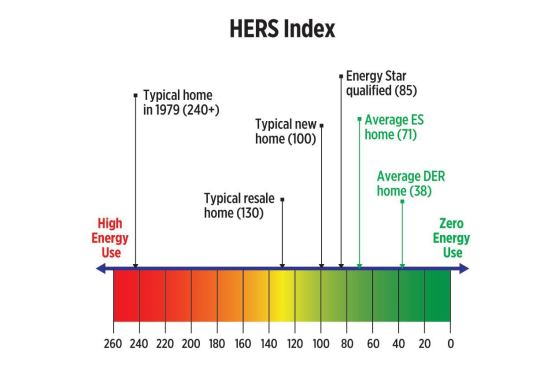

Return on investment. Achieving Energy Star standards took the homes from HERS scores in the 180 range to the low 70s. The Energy Star homes initially operated at an estimated average cost of $7,842 per year, and that was reduced to an estimated average cost of $2,525 per year.

Spending the extra $25,775 on the DER homes further reduced operating cost to an average projected annual cost of $1,519, and reduced HERS scores to an average of 38. The simple payback on that investment is 26 years, but rising utility costs and reduced installation costs (as experience is gained and these practices become more commonplace) could shrink the payback period quickly.

We hope that, with enough successful case studies, the energy-savings payoff of retrofit strategies like this one can become a part of how buyers, lenders, and appraisers assign value to houses. There will always be resistance to improved performance specs that cost more up-front but don’t immediately translate into higher sales prices. But the DER homes have other benefits as well — including durability and controlled indoor air quality — that are more difficult to measure. Over time, we hope builders can overcome resistance by educating clients on all of the benefits of DER.

Matt Berges, Green Housing Manager, and Mandy Metcalf, Affordable Green Housing Center Director, work at Environmental Health Watch, a nonprofit advocacy organization based in Cleveland.